When India became a republic, it didn’t just promise freedom—it promised fairness. The Constitution of India was designed not only to ensure equality for all but also to uplift those who had been left behind for centuries. Let’s explore how our Constitution goes beyond the idea of “equal treatment” and instead focuses on fair opportunity for all, particularly for the Other Backward Classes (OBCs).

Foundation: The Constitutional Backbone

To understand how reservation fits into our democracy, we need to look at key parts of the Constitution:

- The Constitution guarantees equality before the law for all citizens under Article 14.

- Article 15 (1) to (6) prohibits discrimination and allows special provisions for socially and educationally backward classes (SEBCs), Scheduled Castes (SCs), and Scheduled Tribes (STs).

- Article 16 (4) and (4A) talk about equal opportunity in public employment and permit reservations for backward classes in government jobs.

- Articles 338A and 338B created National Commissions to protect the rights of SCs, STs, and Other Backward Classes (OBCs).

These provisions show that the Constitution admits the inequality deprival of opportunities in education, representatives in Government administration, etc., for decades, and the said provisions were introduced with the noble vision of eliminating the said barriers to OBCs.

Institutional Mechanisms for Backward Class Empowerment

To give life to these constitutional guarantees, authorities instituted several supportive bodies and provisions:

- Article 338B led to the creation of the National Commission for Backward Classes (NCBC), a constitutional authority responsible for safeguarding the rights of OBCs.

- Article 340 empowers the President to appoint a commission to examine the status of backward classes. This laid the groundwork for the Mandal Commission, whose recommendations fundamentally shaped OBC reservation policy.

- Article 342A, added later, enables the President to notify SEBCs, thereby giving formal recognition to backward classes at the national level.

Amendments That Shaped Reservation Policy

As society and politics evolved, amendments were made to the Constitution to extend the framework of justice:

- The 1951 First Amendment brought in Article 15(4), which permitted states to implement special measures for the advancement of backward classes.

- The 93rd Amendment (2005) introduced Article 15(5), enabling reservations in private (non-minority) educational institutions.

These amendments reflect the Constitution’s dynamic approach to ensuring representation and opportunity for diverse, disadvantaged groups.

The Supreme Court’s Role

The Supreme Court of India has been instrumental in defining the implementation of reservation policies. Notably through the landmark Indra Sawhney judgment in 1992, where the Court:

- Upheld the 27% reservation for OBCs in jobs.

- Set a cap of 50% on total reservations.

- Clarified that economic backwardness alone cannot be the sole criterion for reservation.

Allowed for ‘creamy layer’ exclusion among OBCs (wealthier individuals within a backward class would not be eligible).

This ruling balanced the principle of merit with the need for social justice, and it remains a guiding precedent.

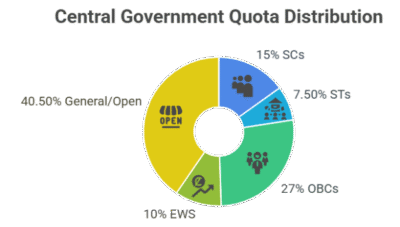

Reservation in Practice: The Numbers Today

Under the central government’s quota system, they structure the reservation as follows:

Additionally, each state has its framework based on local conditions. For instance, Tamil Nadu has a distinct model with 69% reservation. Which operates under a special provision and will be explored in a separate post.