In a country as diverse and layered as India, the idea of social justice cannot thrive without reliable data. Yet, when it comes to caste-based reservations, crucial decisions are often made with outdated or incomplete information. Tamil Nadu’s story is a striking example of how politics, not data, can drive reservation policies—sometimes at the cost of fair justice.

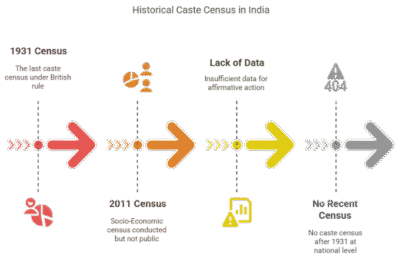

The Missing Numbers: No Recent Caste Census

The last comprehensive caste census in India was conducted in 1931, nearly a century ago, during British rule. Though the 2011 Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) was carried out, the caste-specific data from it have never been officially released. This lack of updated information means that decisions about who is “backward” or “most backward” are often based on assumptions or outdated estimates at the whims and fancies of rulers.

Without reliable data, policies meant to uplift marginalized groups have become political tools rather than instruments of justice.

Tamil Nadu’s Unique Reservation Structure

Tamil Nadu has long been at the forefront of reservation politics. It was the first among the states in India to actively identify and classify Backward Classes (BCs). The First Backward Classes Commission, chaired by A.N. Sattanathan, submitted its report in 1970, proposing a 33% reservation for the Backward Classes. The state government considered this recommendation by raising the reservation from 25% to 31%, and they also revised the SC/ST quota.

But this was just the beginning of a more complex and politically charged evolution.

The Amba Sankar Commission and Internal Conflict

In 1982, Tamil Nadu established the Second Backward Classes Commission under the leadership of J.A. Amba Sankar (IAS, Retd.), to verify the backwardness of communities and suggest improvements. The Commission used three criteria: educational, social, and economic.

However, the Commission ran into major internal disagreements:

- Out of the 20 members, five refused to sign the final report.

- Fourteen members strongly disagreed with the Chairman’s conclusions, accusing the report of containing inaccuracies, manipulations, and discrepancies.

- These 14 members submitted a “Majority Report”, while Amba Sankar’s version was labeled a “Minority Report” by the government. The state accepted the Majority Report and issued orders confirming 50% reservation for Backward Classes and 18% for SC/STs (Vide GO MS No:1564/85 and 1565/85).

- This internal rift highlights how even official commissions can fall prey to communal and political conflicts, especially when lacking strong, up-to-date data.

The Vanniyar Demand and the Rise of MBCs

In the late 1980s, agitations led by Vanniyar Sangam demanded 20% reservation for the Vanniyar community. Amidst widespread protests and violence, the DMK government in 1989 carved out a new category: Most Backward Classes (MBCs), granting them 20% reservation through GO MS No. 242.

This decision heavily relied on the Amba Sankar Minority Report, despite the earlier government rejection of the same data. The 39 communities grouped under MBCs included Vanniyars, while 68 others were classified as “Denotified Communities”.

As per the Amba Sankar Report, the estimated population of Vanniyars was around 13%, while the rest of the MBCs formed just about 7%. These figures were used to justify subgroup-based reservation, but again, these numbers were not validated through any fair, reliable surveys/census.

The Politics of Percentages

In a state like Tamil Nadu, where reservation is 69%, numbers are everything. But without current caste data:

- Population percentages are exaggerated or misquoted.

- Backwardness claims are politically motivated.

- Sub-categorization of communities turns into vote bank politics rather than social justice.

Even as debates rage about adding or removing groups from the OBC/MBC lists, the absence of genuine/correct caste data means such decisions often lack transparency and legitimacy.

Conclusion

When data is ignored, justice becomes a casualty. Tamil Nadu’s story shows how reservation, without transparency or updated caste figures, risks becoming a tool for political manipulation. To restore credibility and fairness, India must prioritize a full, public caste census, because without facts, even the noblest policies meant to uplift the ignored, oppressed people will definitely fail.