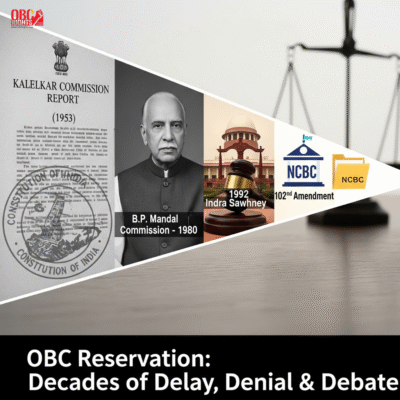

The story of OBC (Other Backward Classes) reservation in India is a journey of long-pending genuine justice, social recognition, and constant reform. It’s a timeline filled with commissions, court rulings, and constitutional changes — all aimed at leveling the playing field for communities that have historically been left behind. The question is whether justice is rendered to OBC Communities?

1953: The First Step – Kalelkar Commission

The Indian government took its first major step in 1953 by setting up the Kalelkar Commission. This was the first time backward classes — apart from SCs (Scheduled Castes) and STs (Scheduled Tribes) — were just acknowledged at the national level. However, the commission’s report was ambiguous and did not serve any purpose.

1980: The Mandal Commission – A Game Changer

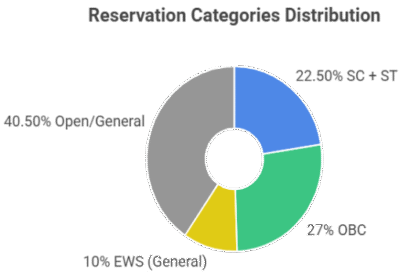

In 1979, the Mandal Commission was set up to examine the status of socially and educationally disadvantaged communities. The 1980 report of the commission estimated that OBCs constituted nearly 52% of India’s population. It identified 1,257 communities as backward and recommended 27% reservation for OBCs in government jobs and educational institutions.

The total reservation, including SC/ST quotas, would rise to 49.5%, staying just under the Supreme Court’s 50% cap. These changes were backed by:

- Article 16(4): Reservation in public employment.

- Article 15(4): Reservation in educational institutions.

But the Mandal Commission Report was kept in cold storage / ignored till 1990.

1992: The Indra Sawhney Judgment – “Creamy Layer” Introduced

The historic Indra Sawhney judgment, widely known as the Mandal Case, marked a significant turning point. The Supreme Court upheld 27% OBC reservations but excluded the “Creamy Layer” — the advanced sections among OBCs — alleging that benefits reached the most disadvantaged.

This case also fixed the 50% cap on total reservations and clarified that economic status alone cannot be the reservation basis.

2018: A Stronger NCBC – But Still Weak in Action

The 102nd Constitutional Amendment Act gave constitutional status to the National Commission for Backward Classes (NCBC). Earlier, a statutory body under the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, it now has more powers on paper, but in reality, its effectiveness remains questionable due to limited action and autonomy. It appears that the NCBC has become ornamental, without teeth.

2019: EWS Reservation

The 103rd Amendment introduced a 10% quota for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) in the General Category, using only economic criteria — a first in India’s reservation policy. The people who are not listed/found in any reservation category and the annual income is less than Rs 8 Lakhs come under this category.

However, it breached the 50% cap, included all communities, and, critics argue, weakened the core purpose of affirmative action, which is to address social and educational disadvantage, not just poverty.

On What Basis is Reservation Given?

Reservation for OBCs and SEBCs is based on social and educational backwardness, not just income. Key factors include:

- Low social status

- Poor education levels

- Underrepresentation in jobs/politics

- Nature of work (like manual or agricultural jobs)

- Inadequate housing or land

- Low family income

- Backward region of residence

Conclusion: A Journey Still in Progress

From Kalelkar to Mandal, and now to the controversial EWS, the OBC reservation story reflects India’s continuous struggle to achieve real social justice. While the Constitution clearly prioritizes social and educational backwardness, recent policies like EWS raise tough questions about the direction of affirmative action.

The fight is not just for representation but for fairness, equity, and dignity — values that can only be upheld if policies remain true to their original intent.

In every State or Government of India, the interests of OBCs are ignored.