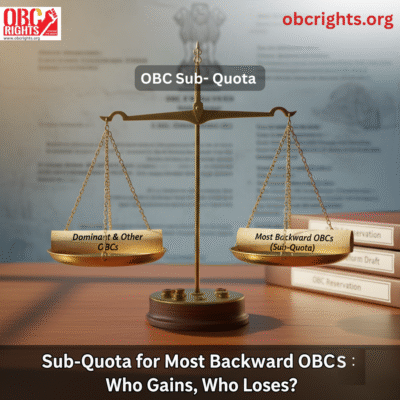

For years, the debate around OBC reservation has revolved around fairness, representation, and internal inequality. Now, the proposal of a Sub-Quota for the Most Backward segments within the OBC category has re-ignited a serious policy discussion. The idea is simple on the surface — divide the OBC quota internally so that the most disadvantaged communities receive a fair share. But the implications are not simple at all. Who benefits? Who resists? And what does this move mean for social justice?

Why the Demand for Sub-Quota Emerged

OBC reservation was introduced to uplift historically marginalized communities. However, over the decades, a small number of relatively advanced OBC castes have cornered a major share of the benefits in education, government jobs, and politics. Most Backward OBCs, especially nomadic, artisan, and denotified groups, continue to remain underrepresented.

Several surveys and commissions — including the Mandal Commission, the Rohini Commission, and state-level studies — have highlighted this internal imbalance. For many communities, the reservation policy has become symbolic, not transformational.

That is where the idea of a Sub-Quota enters the debate — a targeted mechanism to ensure that the Most Backward OBCs are not drowned out by dominant OBC groups.

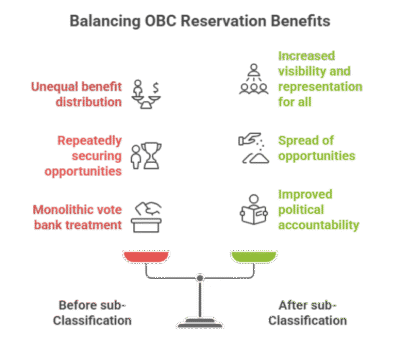

Who Gains From a Sub-Quota?

1. Most Backward OBCs finally get visibility

Communities with minimal representation in jobs and education could secure a dedicated share of reservation benefits.

2. Balanced distribution within the OBC reservation

Instead of dominant OBCs repeatedly securing seats, opportunities would spread to neglected castes.

3. Improved political accountability

Governments can no longer treat OBCs as a monolithic vote bank. The data on internal inequality becomes harder to ignore.

4. Gender equity within the reservation

Women from the Most Backward OBC segments could benefit from layered mobilization.

Who May Lose or Resist?

1. Politically powerful OBC castes

Communities that have historically benefitted – due to social capital, education, networks, and awareness – may resist changes that reduce their share.

2. States with no internal classification

In states where OBCs are treated as a single block, implementation may trigger conflicts.

3. Political parties with upper-layer OBC leadership

Redistribution may weaken their core support base.

4. Lack of reliable caste-based data

Without a caste census or transparent socio-educational statistics, designing a fair sub-quota is challenging.

A Sub-Quota Battle in the Courts and Politics

The middle of this policy debate is where the keyword Sub-Quota becomes politically sensitive. Some state governments, like Bihar, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka, have already adopted internal groupings for OBC reservation. Others are waiting for central direction or the outcome of the Rohini Commission report.

Legal experts point out that any sub-allocation will have to pass the test of reasonable classification, proportional representation, and constitutional backing. The Supreme Court’s past judgments suggest that sub-division is permissible as long as it addresses real inequality.

However, without strong data, the move could lead to new litigation rather than justice.

The Bigger Question: Representation or Tokenism?

Will sub-quota solve the core issue, or merely shift the fault lines? Implementation must go beyond numbers and touch:

- Access to quality education

- Awareness of rights and schemes

- Localised recruitment and scholarship drives

- Political participation at the panchayat and state levels

- Support systems for first-generation learners

Without these, sub-quota may end up as another policy in the file, not a change on the ground.

The Way Forward

As the debate reaches its conclusion stage, one thing is clear: the Sub-Quota question is not just about percentages. It’s about recognition, redistribution, and real empowerment. The Most Backward OBCs have waited for decades to be seen within a category that was supposed to uplift them.

The success of this move depends on three critical factors:

- Accurate caste-based data to define beneficiaries

- Legal backing that cannot be overturned easily

- Political will to face resistance from the dominant OBC groups

The verdict is still open. But the question remains — if justice within a reservation is ignored, can the reservation itself achieve its purpose?

If a reservation doesn’t actually help the people who need it most, then what is the use of having it at all?