Universities are expected to be the spaces where equality and diversity find real meaning. Yet the latest government figures reveal a different reality. In Central Universities, the presence of OBC and ST faculty at senior levels is shockingly low. Data placed before Parliament shows that close to 80% of OBC professor seats and 83% of ST posts are still unoccupied. These numbers are not just statistics—they highlight how systemic exclusion continues to define India’s higher education. Even the meritorious candidates are sent out by stamping that they are “Not Found Suitable (NFS)”.

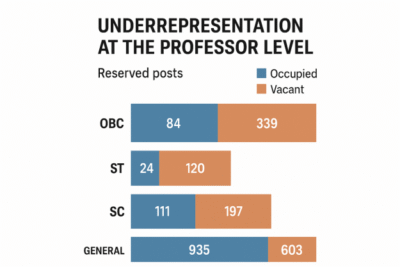

Underrepresentation at the Professor Level

At the professor level, the data is stark. Only 84 out of 423 reserved OBC posts are currently occupied. For STs, only 24 of 144 posts are occupied. Even for SCs, just 111 of 308 professor positions are filled. In comparison, the general category has 935 of 1,538 posts filled — still leaving a significant 39% vacant but far better than the abysmal figures for marginalized groups. The position of OBCs in the graph should be the eye-opener and self-introspection (for every OBC Citizen).

This imbalance shows that while vacancies exist across the board, they disproportionately affect communities meant to be protected by reservation policies.

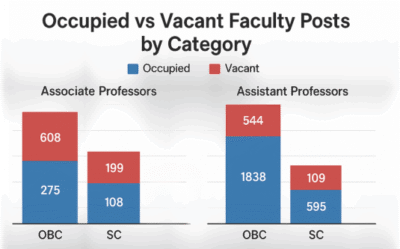

Associate Professor Posts: A Growing Concern

The crisis is not just statistical; it points to systemic barriers. At the Associate Professor level, large numbers of posts also remain vacant. Out of 883 sanctioned posts, OBCs have secured only 275, while STs hold merely 108 of 307. At the assistant professor level, however, the picture looks slightly better: 1,838 of 2,382 OBC posts are filled, along with 595 of 704 for STs.

This contrast reveals a critical bottleneck. Entry-level posts show some progress, but as one moves up the academic ladder, representation collapses. Promotion hurdles, opaque selection procedures, and the recurring claim that candidates are “Not Found Suitable” create roadblocks.

Why Are Vacancies Left Unfilled?

The Ministry of Education has stated that faculty selection depends on open advertisements and the recommendations of selection committees. Vacancies persist when no candidates are “found suitable.” But this explanation raises more questions than answers.

There is no centralized record of how many candidates are rejected under the “Not Found Suitable” tag. Without transparency, it is difficult to determine whether these decisions are based on genuine criteria or on implicit biases. This lack of accountability helps explain why such a high vacancy in central universities continues despite a large pool of qualified candidates. The integrity and fairness of the selection process and selection committees are in question.

The Larger Structural Problem

These vacancies are not isolated administrative issues; they reflect structural barriers. Marginalized scholars often face limited access to research funding, mentorship, and academic networks. Without these, advancing to senior faculty roles becomes an uphill task.

The absence of OBC and ST professors at higher ranks also sends a discouraging signal to students. When classrooms lack role models from their communities, students may feel alienated in spaces that should empower them.

Central Universities at a Crossroads

The growing vacancy in central universities undermines the core purpose of reservation. The policy was designed to ensure equal opportunity, not just at the entry level but across all positions of influence. Unless the government and institutions act fairly and decisively, this imbalance will persist, weakening both social justice and academic excellence.

Filling these posts is not about charity. It is about fulfilling a constitutional mandate and ensuring that universities truly reflect the diversity of India. Transparent recruitment, special promotion drives, and monitoring of vacancy data are urgent needs. As done for backlog vacancies, every year a special recruitment must be conducted to fill the vacancies.

Structural Barriers and Urgent Reform

Faculty vacancies highlight deep structural hurdles. OBC and ST scholars often lack access to research support, mentorship, and networks, making senior positions harder to reach. Their absence at higher ranks also leaves students without relatable role models. It very much prevents OBCs/STs role in framing curriculum, teaching methods, and various strategies that have in fact on students’ performance.

This vacancy in central universities defeats the purpose of reservation, which was meant to secure equal representation at every level. Transparent recruitment, focused promotion drives, and strict monitoring are essential to build universities that reflect India’s true diversity. The vision of the Constitutional Framers should not be thrown away by anyone that too at the place where the future pillars (youth) are groomed.

The Future of Equality Depends on Action Today

Parliamentary data exposes a crisis that demands immediate attention. When 80% of OBC and 83% of ST faculty positions remain unfilled, the goal of equal representation in higher education is still far from reality. Central Universities must confront this failure head-on by creating systems that not only recruit but also support marginalized faculty at every level.

Representation matters—not only for fairness but also for shaping inclusive institutions that inspire every student. Unless urgent action is taken, the empty posts will remain a reminder of unkept promises.

Vacancies don’t just leave seats empty—they erase or shatters futures. It’s time to ask why? Where is the problem? What is the remedy?