When Justice B.V. Nagarathna said that “women are the largest minority in India,” she wasn’t speaking of numbers but of power; it was not just a courtroom remark—it was a mirror held up to our democracy. Women make up nearly half the population but hold barely one-eighth of seats in Parliament. The Supreme Court’s recent notice to the Centre, asking why the reservation for women in India is still not implemented, has reopened an urgent national question—when will equality become real?

The Law that Waits for Action

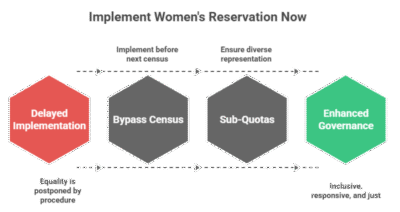

The Women’s Reservation Act, passed in 2023, promises 33 per cent reservation for women in the Lok Sabha and State Assemblies. But the law’s implementation is tied to the next census and delimitation exercise, expected only after 2027. In simple terms, the promise of equality has been protracted for at least two more elections.

Equality Delayed, Democracy Diminished

Justice Nagarathna’s remark reminds us that equality cannot be postponed by procedure. The reservation for women in India is not a political favour—it is a constitutional duty drawn from the Preamble’s pledge of social and political justice. Each delay in implementing is a continuing a silent injustice: women vote in equal numbers, yet remain sidelined when it comes to shaping laws.

The Representation Gap

The 18th Lok Sabha has just 74 women MPs—around 13.6%. That is less than half the global average. At the state level, many assemblies have fewer than 10% women MLAs. These numbers show why the reservation for women in India is essential. Greater representation means policies that better reflect real social priorities—education, safety, and welfare.

Why Reservation for Women in Parliament Matters?

The reservation for women in India is not just about numbers—it’s about transforming the nature of governance. When more women enter Parliament, decision-making becomes more inclusive and responsive to real social needs. Evidence from states and panchayats shows that women leaders tend to:

- Women ensures the health, education and well-being of a/every family.

- Prioritise education, healthcare, and basic amenities over partisan politics.

- Push for stronger laws on safety, nutrition, and welfare.

- Ensure better fund utilization and reduce corruption through transparency.

- Represent the concerns of women, children, and marginalized communities more effectively.

- Inspire greater participation of young women in politics and public life.

- To ensure a confidence all trust over the governance, security of women and justice to the weaker sections.

When women share power, the nation gains balance, empathy, and long-term vision—qualities that strengthen democracy itself. The reservation for women in India is, therefore, not just a policy of inclusion but a pathway to better governance and social justice.

Beyond the Numbers: Representation Within Representation

Even when a 33 per cent reservation for women becomes a reality, a deeper issue will remain—who will benefit from it? Without sub-quotas, there is a risk that political parties will field only upper-caste or elite women, replicating existing hierarchies under a new label. The conversation must therefore expand beyond gender to include caste and class within women’s representation. True social justice demands that the law uplift women from all communities, including OBC, SC, and ST backgrounds. The neglected communities should not be neglected forever.

Conclusion

The reservation for women in India is more than a legal reform; it is a moral correction. The Supreme Court’s observation is a reminder that half of India still waits for its rightful space in power. Political equality cannot wait for census maps—it must begin now, with the will to honour the Constitution’s promise.

If equality is already enshrined in our Constitution, why should women still wait for permission endorsement to claim it?

How long will promises of representation remain trapped in procedure?

It’s time to ask — if not today, then when?

Please mail your comments on this blog to: obcrights.sfrbc@gmail.com